In the aftermath of the Second World War, some countries advocated the sharing of oceanographic knowledge on a global scale. However, it was not until December 1960 that the Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission of UNESCO – the first body responsible for strengthening intergovernmental co-operation in the marine sciences – was created.

By Jens Boel - A Danish historian and UNESCO's Chief Archivist from 1995 to 2017, he initiated the UNESCO History Project in 2004, to encourage the use of its archives. Boel's next book, Exploring the Ocean, on the history of the IOC, will be published in 2022.

Between 1959 and 1965, forty-five research vessels sailing under fourteen different flags explored the Indian Ocean. Atlases, maps and scientific studies resulting from this expedition revolutionized geological, geophysical and marine-biological knowledge of this ocean. The monsoon and its variations were better understood, and food resources and mineral deposits discovered. The expedition also enabled countries like India, Indonesia, Pakistan and Thailand to build or expand their marine science infrastructures. The International Indian Ocean Expedition (IIOE) was unique, and at the time, was the biggest ocean exploration ever launched.

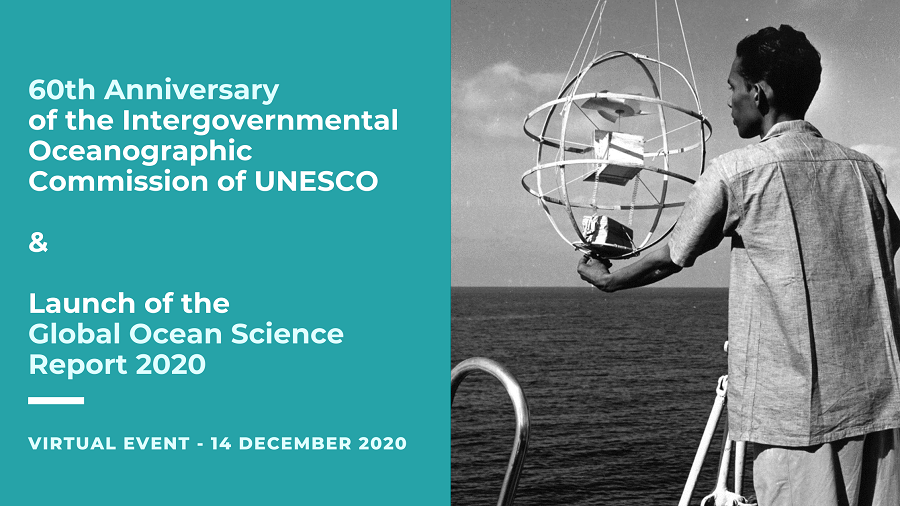

Co-ordinating this unprecedented international research effort was the first major activity of the Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission (IOC), which celebrates its sixtieth anniversary on 14 December 2020.

The meteorological observation balloon equipped with a transmitter being released in 1963,

as part of the International Indian Ocean Expedition (1959-1965),

coordinated by the IOC. © UNESCO, Ministry of Information, Government of India

Knowledge sharing

The journey towards the creation of the IOC had been a long one. Already, at the first session of the General Conference in November 1946, India had proposed the creation of an institute of oceanography and fisheries to study the Indian Ocean. However, the first political initiative to make UNESCO include marine science activities in its programme came from Japan. In 1952, the country presented a draft resolution with the purpose of engaging UNESCO to promote international co-operation on oceanography. This was done with the view to optimize the use of marine resources – fisheries, minerals and energy – and thereby “provide a basis for the peaceful coexistence of all mankind”.

Never before had ocean sciences been so high up on the international political agenda

The proposal was well-received, but did not lead to any significant commitment of UNESCO’s resources. The breakthrough came at the next session of the General Conference, in 1954, when Japan again proposed that UNESCO should launch a marine sciences programme.

The International Geophysical Year (IGY), from July 1957 to December 1958, was an essential part of the dynamics that eventually led to the creation of the IOC. During this time, the IGY formed the framework for a vast range of global geophysical activities.

The best known of these is the Soviet launch of Sputnik I, the first artificial satellite, but the IGY also greatly enhanced the interest of the international community in oceanographic projects.

This interest was driven by a variety of motivations – in particular an interest in waves, currents and tides; concerns about radioactive pollution; the search for food and other resources in the ocean; the wish to explore the deep sea bed, and to understand the interactions between the ocean and the atmosphere. The idea that it was necessary to collect and share data on a global scale on all these subjects was gradually gaining ground.

In July 1960, UNESCO convened an oceanographic conference in Copenhagen, Denmark. Delegations from thirty-five countries gathered with representatives of other United Nations agencies and international organizations. They recommended that UNESCO establish a new intergovernmental body to promote the scientific investigation of the ocean.

The proposal was accepted in December 1960 by the General Conference. It was unprecedented. Never before had ocean sciences been so high up on the international political agenda.

From idea to action

In the beginning, the IOC’s place in UNESCO was far from obvious. Some of the scientists who took the initiative to create the Commission would have preferred the establishment of a separate United Nations agency, the World Oceanographic Organization (WOO). Other UN agencies questioned why UNESCO should take the lead in this particular field. For instance, both the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) and the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) put forward their expertise in fisheries and meteorology respectively.

Issues about ‘who should do what’ have remained a challenge over the years, but most IOC activities have been carried out in close co-operation with UN agencies and other stakeholders. The IOC also has a recognized role in the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), the global legal framework for the ocean.

Another challenge was the scope of the mandate of the new Commission. One of the debates at the beginning was whether it should mainly support the most advanced research to push the boundaries of human knowledge of the ocean as quickly as possible, or concentrate on building the oceanographic capacities of developing countries. In reality, the IOC has been doing both, with a greater emphasis on capacity development today.

During the sixty years of its existence, the IOC, which now has 150 Member States, has gradually reoriented its emphasis towards systematic, sustained observation systems – such as the Global Ocean Observing System (GOOS), created in 1991 – and the overarching concept of sustainable development. At the same time, research and knowledge sharing on all ocean science-related topics, such as The Global Ocean Science Report, remain the leitmotif of its work.

Research and knowledge sharing on all ocean science-related topics remain the leitmotif of the IOC’s work

An early accomplishment was the establishment, in 1961 of the International Oceanographic Data and Information Exchange (IODE), which remains a cornerstone programme of the IOC. Among its projects since 2009, is the Ocean Biodiversity Information System (OBIS).

Another highlight of the IOC’s activities is the Pacific Tsunami Warning and Mitigation System (PTWS). Created in 1965 to save lives, it has since served as a model for other exposed regions – including the Indian Ocean, the Caribbean, the North-East Atlantic and the Mediterranean.

The IOC ensured the leadership of the International Decade of Ocean Exploration (1971-1980), to raise awareness of the importance of ocean science. So it was only natural that fifty years later, the Commission took the lead when the UN proclaimed a Decade of Ocean Science for Sustainable Development from 2021 to 2030.

(This article was originally published on The UNESCO Courier: https://en.unesco.org/courier/news-views-online/making-ocean-commission)